$100B Oil Bet Nobody's Taking

The only report you must read - Why Venezuela's reserves can't tempt Big Oil ?

On January 9, 2026, the White House convened the largest gathering of oil executives in recent memory to pitch a once-in-a-generation opportunity: rebuild Venezuela’s shattered energy infrastructure and unlock the world’s largest proven petroleum reserves. The ask? At least $100 billion in investments. The response? Calculated silence wrapped in diplomatic caution.

“If we look at the commercial constructs and frameworks in place today in Venezuela, today it’s uninvestable” ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods told the room, his words cutting through the optimistic framing like a seismic survey revealing no recoverable reserves.

This wasn’t mere negotiating posture. The arithmetic of Venezuela’s energy sector tells a story of spectacular decline that no amount of capital can quickly reverse.

The Numbers Behind the Decline

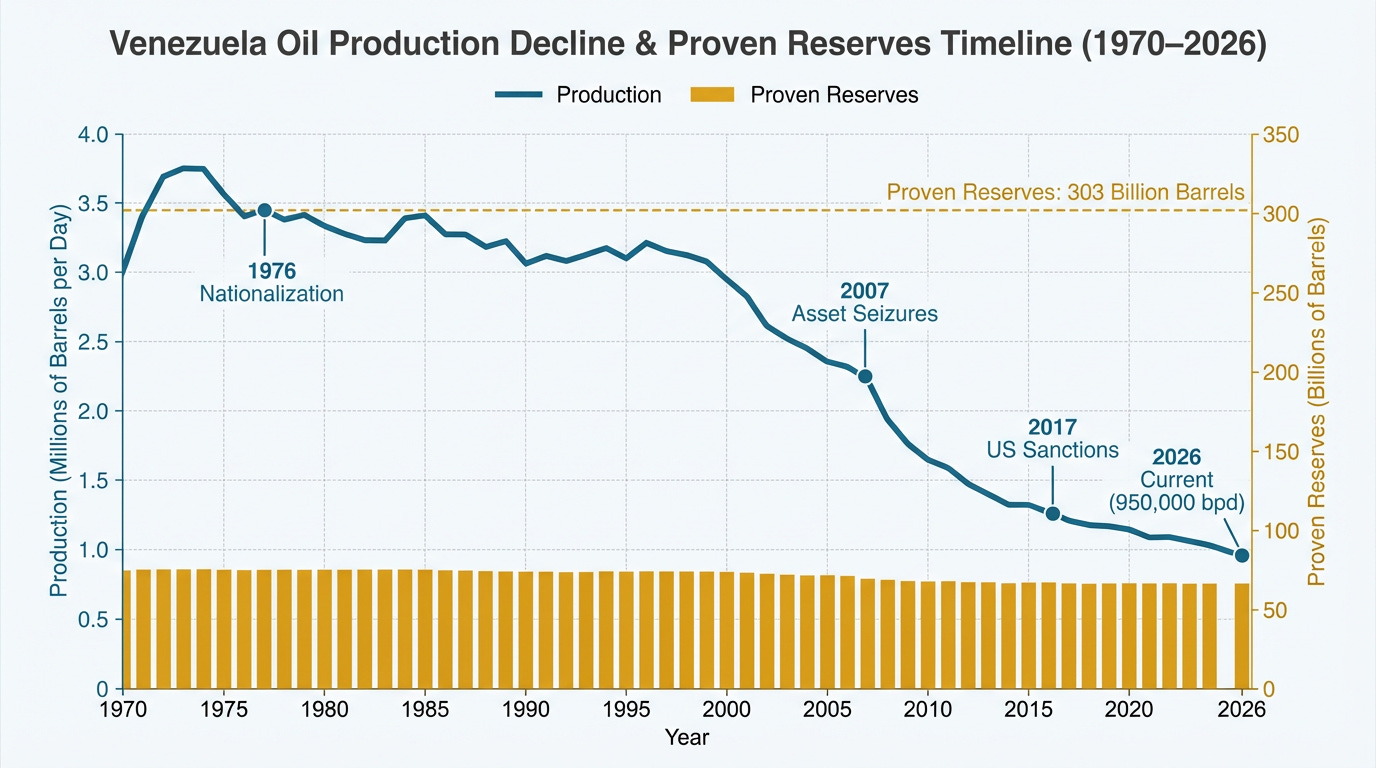

Venezuela sits atop 303 billion barrels of proven reserves, surpassing Saudi Arabia’s 267 billion. Yet the country currently produces less than 950,000 barrels per day (bpd), down from 3.5 million bpd in the 1970s. That’s a 73% production collapse despite reserves that should make it an energy superpower.

The infrastructure decay explains the paradox. Refineries operate at roughly 20% capacity. Critical pipelines leak crude into soil and waterways. Skilled petroleum engineers and geologists emigrated years ago, taking institutional knowledge with them. Power grid failures regularly shut down pumping operations. PDVSA, the state oil company, carries debt exceeding $60 billion with no clear path to restructuring.

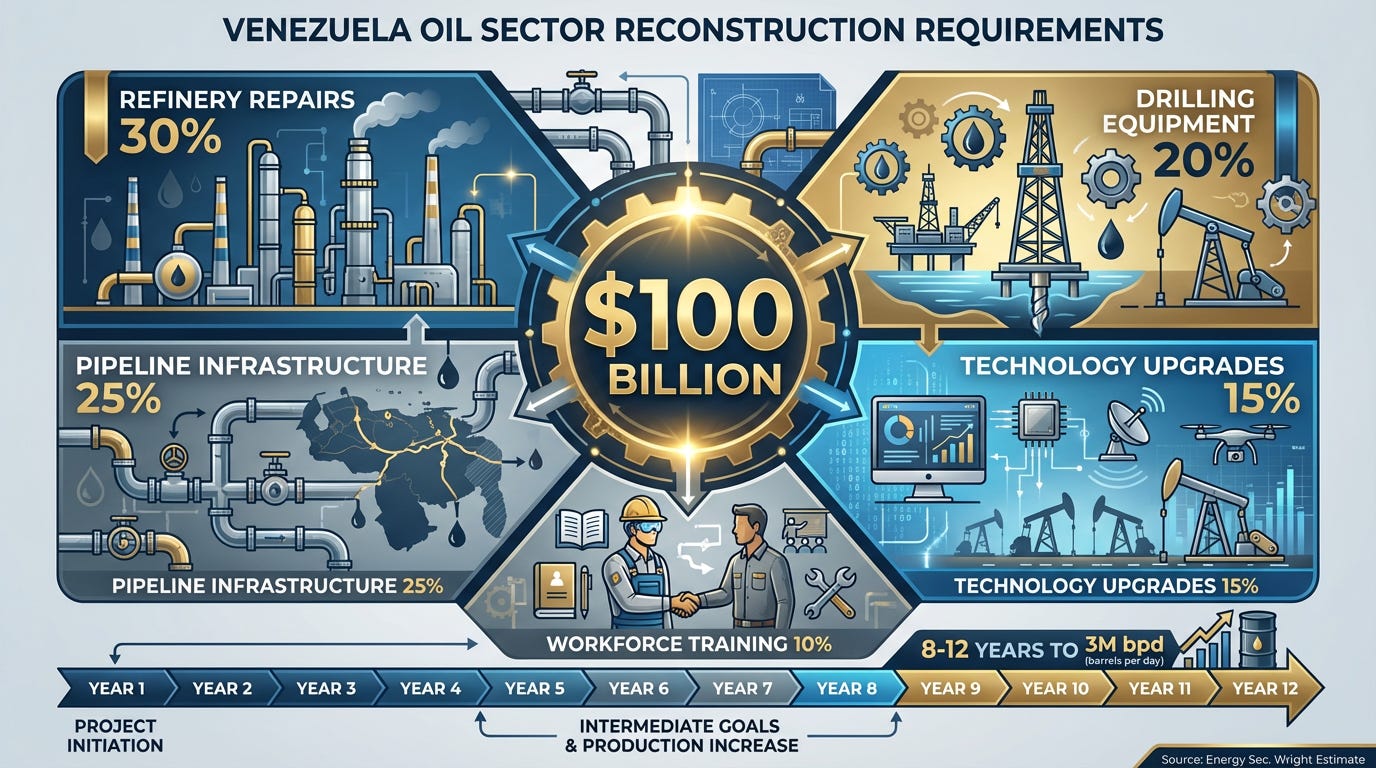

Energy Secretary Chris Wright clarified post-meeting that the $100 billion figure represents estimated reconstruction costs over a decade, not committed capital. Even under optimistic scenarios, returning Venezuela to 3 million bpd would require eight to 12 years of sustained investment.

That timeline assumes perfect execution,no further nationalizations, consistent legal framework, stable governance, and uninterrupted operations. Venezuela’s 50-year petroleum history offers zero precedent for this scenario.

Breaking Down the $100 Billion

Industry analysts estimate reconstruction would require:

Refinery repairs and upgrades: $30 billion to restore processing capacity and meet modern environmental standards. Venezuela’s refineries were built primarily in the 1950s-70s and lack modern catalytic cracking units necessary for heavy crude processing.

Pipeline and transportation infrastructure: $25 billion for new pipelines, storage facilities, and export terminals. The existing system experiences chronic leaks and lacks the capacity to handle increased throughput.

Drilling equipment and wellhead restoration: $20 billion to replace corroded equipment, drill new wells, and implement enhanced recovery techniques necessary for Venezuela’s viscous heavy crude.

Technology and digitalization: $15 billion for modern reservoir management systems, automation, and the digital infrastructure major operators consider standard.

Workforce development: $10 billion for training programs, attracting skilled workers, and rebuilding the institutional capacity that PDVSA lost through decades of brain drain.

These aren’t independent cost centers. Infrastructure repairs reveal additional problems. Workforce shortages slow construction timelines. Technology upgrades require stable power grids that don’t exist. Each element depends on others in a complex reconstruction sequence that multiplies both costs and timelines.

The Corporate Responses: A Study in Strategic Caution

The meeting assembled representatives from ExxonMobil, Chevron, ConocoPhillips, Shell, Continental Resources, Hilcorp, Halliburton, Valero, Marathon, Repsol, Eni, Trafigura, and over a dozen smaller independents. Their collective market capitalization exceeds $1.5 trillion. Yet the concrete commitments totaled near zero.

ExxonMobil: The Skeptic

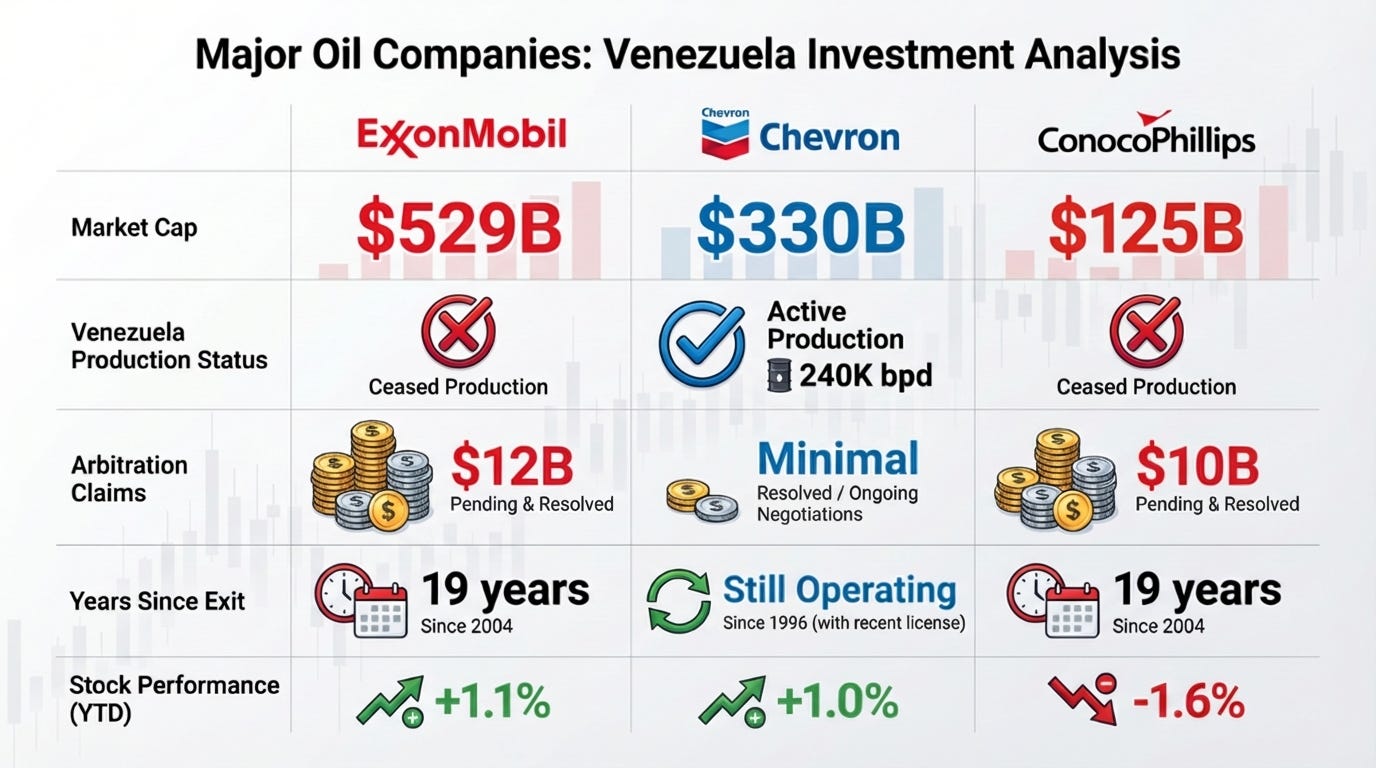

Market cap: $529.4 billion | Q3 2025 earnings: $7.5 billion

CEO Darren Woods outlined the clearest position. ExxonMobil exited Venezuela in 2007 after the government seized assets estimated at $12 billion. Through two decades of arbitration, the company has recovered roughly $800 million. Woods emphasised that re-entry requires “significant changes” to commercial frameworks, hydrocarbon laws, and investment protections.

The company committed to sending technical assessment teams to evaluate infrastructure conditions, but stopped well short of capital allocation. Exxon’s stock closed at $124.61 on January 9, up 1.1%, suggesting investors viewed the cautious approach favourably.

Woods’s framing matters because Exxon operates globally across dozens of challenging jurisdictions. When a company accustomed to Nigerian deepwater projects and Kazakhstani megafields calls Venezuela “uninvestable,” it signals fundamental commercial barriers, not risk aversion.

Chevron: The Incumbent

Market cap: $329.6 billion | Current Venezuela production: 240,000 bpd

Chevron represents the only major U.S. oil company still operating in Venezuela through joint ventures with PDVSA. Vice Chairman Mark Nelson offered the meeting’s sole specific production commitment: increasing output by 50% within 18-24 months from existing operations, potentially reaching 360,000 bpd.

This matters because Chevron can expand without massive new capital by optimizing existing wells, improving recovery rates, and repairing rather than replacing infrastructure. It’s incremental growth from a known baseline, not transformational investment in untested projects.

Chevron’s 103-year history in Venezuela gives it unmatched geological knowledge and operational relationships. The company views Venezuela as a long-term strategic position worth maintaining through difficult periods. Stock performance reflected this positioning, closing at $162.11, up 0.97%.

ConocoPhillips: The Burned Creditor

Market cap: $124.6 billion | Outstanding arbitration claims: ~$10 billion

CEO Ryan Lance congratulated the administration on recent developments but immediately pivoted to structural concerns. ConocoPhillips holds approximately $10 billion in unpaid arbitration awards from the 2007 nationalization, representing one of the largest unresolved commercial disputes in petroleum history.

Lance called for wholesale restructuring of PDVSA itself, arguing the state oil company represents a barrier rather than a partner. He emphasized that banking sector involvement would be necessary to restructure Venezuela’s broader debt and provide project financing.

ConocoPhillips closed at $97.51, down 1.6% on meeting day, the only major decliner among participants. Markets appear to price in continued legal battles rather than near-term production increases.

Shell: The Returnee

European major with historic Venezuela presence

Shell CEO Wael Sawan struck a notably different tone from American counterparts. The company exited Venezuela during 1970s nationalizations, surrendering roughly 1 million bpd in production. Sawan indicated Shell has “a few billion dollars’ worth of opportunities to invest” pending permit approvals.

This enthusiasm likely reflects Shell’s decades-long absence. Unlike Exxon and ConocoPhillips, Shell lacks recent asset seizure scars. The company views Venezuela as a potential re-entry opportunity rather than a return to the scene of losses. European energy majors also operate under different political and regulatory constraints than U.S. firms, potentially offering flexibility American companies lack.

The Independents: Faster but Smaller

Continental Resources, Hilcorp Energy, Raisa Energy, Tallgrass Energy, and HKN Inc. represented a different investment thesis. These companies lack the scale to deploy tens of billions but can move capital faster than corporate boards at supermajors.

Harold Hamm of Continental Resources called Venezuela’s reserves “very exciting” while acknowledging “challenges.” Jeffery Hildebrand of Hilcorp declared his company “fully committed and ready to go.” Yet neither specified dollar amounts or project timelines.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent revealed the administration’s strategy shift the day before, noting that “big oil companies who move slowly, who have corporate boards, are not interested,” while claiming “independent oil companies and individuals, wildcatters—our phones are ringing off the hook.”

This pivot from supermajors to independents signals recognition that the $100 billion target won’t materialize from traditional sources. Smaller operators can pioneer projects, establish proof-of-concept operations, and potentially pave the way for larger players. Or they become cautionary tales about rushing into unstable jurisdictions.

The Heavy Crude Challenge

Venezuela’s petroleum isn’t easily substitutable. The country produces primarily heavy, high-sulfur crude requiring specialized refining infrastructure. U.S. Gulf Coast refineries configured for this feedstock represent the natural market, but they’ve spent years adapting to lighter shale oil.

Heavy crude trades at significant discounts to benchmark Brent and WTI prices because fewer refineries can process it. Venezuela’s Orinoco Belt crude averages 8-10° API with 2.5-3.5% sulfur content, compared to conventional oil’s 30-40° API and less than 0.5% sulfur. This viscosity requires heat, diluent, or upgrading before transport, creating permanent cost disadvantages that affect every economic model.

What the Market’s Actually Saying

Equity markets provided clearer signals than executive statements. Exxon and Chevron posted modest gains (1.1% and 0.97%), reflecting investor approval of cautious approaches. ConocoPhillips declined 1.6%, suggesting markets don’t expect near-term resolution of arbitration claims. Oil futures barely reacted—Brent crude held steady around $75 per barrel. The market has correctly assessed this as years away from impacting global supply.

The Legal Framework Nobody’s Built

Woods’s emphasis on “durable investment protections” points to the most significant barrier: Venezuela’s legal framework remains fundamentally unchanged since 2007 nationalizations. Current law requires PDVSA majority stakes in all petroleum projects. The 2001 Hydrocarbons Law restricts foreign ownership and mandates technology transfer.

Changing these laws requires Venezuelan National Assembly action, public consultation, and potentially constitutional amendments. The interim government has made no moves toward these reforms. ConocoPhillips CEO Lance called for “restructuring the entire Venezuelan energy system including PDVSA”—not a regulatory tweak, but fundamental reorganization of the country’s primary economic institution. The timeline for such restructuring extends years, even under optimal conditions.

The Export-Import Bank Question

Energy Secretary Wright floated using the Export-Import Bank to provide federal loan guarantees for Venezuela projects, effectively transferring risk from corporate balance sheets to taxpayers. This trial balloon was quickly withdrawn but reveals the administration’s recognition that purely commercial investment won’t materialize without public risk-sharing.

What Investors Should Monitor

Several concrete indicators will signal whether this opportunity progresses beyond rhetoric:

Legislative action in Venezuela: Watch for proposed amendments to hydrocarbon laws or PDVSA restructuring plans. Without legal framework changes, everything else is premature.

Technical assessment reports: Exxon’s promised evaluation teams will provide independent estimates of infrastructure conditions and realistic production timelines.

OFAC licensing activity: The volume and terms of licenses issued by the Office of Foreign Assets Control will indicate how seriously the U.S. government views near-term investment prospects.

Actual capital deployments: Watch for companies moving from expressions of interest to specific project funding and equipment orders.

Production data: Chevron’s 50% increase commitment provides a near-term benchmark. If the company achieves 360,000 bpd within 18-24 months, it validates that incremental expansion is possible.

The Reality Check

Venezuela’s energy sector decline resulted from decades of mismanagement, corruption, underinvestment, brain drain, and sanctions. Reversing this trajectory requires sustained capital deployment, political stability, legal certainty, skilled workforce reconstruction, and infrastructure modernization occurring simultaneously over years.

The January 9 meeting produced zero binding financial commitments. Energy Secretary Wright’s eight-to-twelve-year timeline to 3 million bpd assumes best-case execution. Petroleum megaprojects routinely experience delays and cost overruns in stable jurisdictions with established legal frameworks. Venezuela offers none of these advantages.

For energy investors, the key takeaway is temporal. This isn’t a 2026 story or even a 2027-28 narrative. If Venezuela’s oil sector reconstruction happens, it unfolds across a decade-plus timeline with multiple points where things could go wrong. That’s not pessimism; it’s petroleum industry reality.

Follow the Energy

The intersection of global oil markets, corporate strategy, and resource development creates opportunities and traps that most coverage misses until they’ve already played out. Venezuela represents just one chapter in a broader story of how energy companies navigate risk, deploy capital, and balance shareholder returns against strategic positioning.

Subscribe to this Substack for ongoing coverage of developments most outlets won’t analyse until they’ve moved markets:

Tracking actual capital deployments versus rhetorical commitments

Deep-dive financial analysis of energy companies’ strategic decisions

Technical assessments of oil & gas projects and their economic viability

Coverage of how infrastructure constraints and geology affect investment outcomes

Flux Kinetics - Where energy meets intelligence,

Wassim C.

This content is for educational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or tax advice. All opinions and analyses are my own, and any actions you take are at your own risk after consulting an appropriate professional.